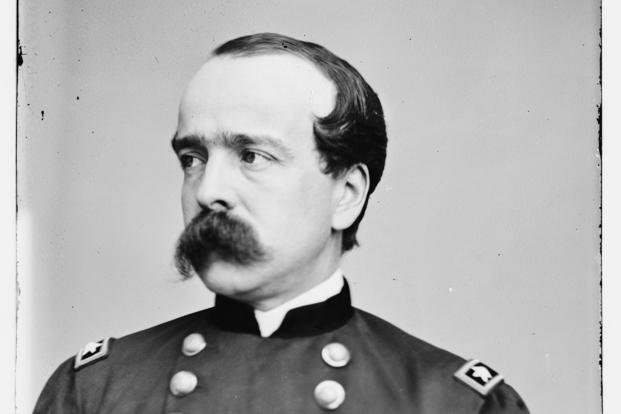

Daniel Butterfield could not read or write music, but he knew what he liked. A brigadier general in the Union Army who would go on to receive the Medal of Honor in 1892 for gallantry during the Civil War, Butterfield was not particularly enamored with the bugle call that signaled lights out to U.S. troops at the end of the day.

One day in July 1862, Butterfield summoned his brigade's bugler, Oliver Willcox Norton, and suggested he play a series of notes that were less formal than the official call of "Extinguish Lights." Norton followed Butterfield's instructions, and after a few tweaks, what resulted was the U.S. military's most popular bugle call of them all: Taps.

"There is something singularly beautiful and appropriate in the music of this wonderful call," Norton would later recall in an undated article called "The Origin of 'Taps'". "Its strains are melancholy, yet full of rest and peace. Its echoes linger in the heart long after its tones have ceased to vibrate in the air."

The easily recognizable 24 notes of taps have become so ingrained into military life that every U.S. service member, veteran, their families and even the public at large have become intimately familiar with them. While originally intended to encourage service members to go to sleep -- it is sounded at 9 p.m. on U.S. bases -- it is also now synonymous with military funerals and wreath-laying ceremonies.

It is the only bugle call in America’s armed forces with multiple purposes, according to former Taps for Veterans President Jari Villanueva.

"I strive to play that call as perfectly as I can," Villanueva, who estimated he has played taps thousands of times since he first sounded it as a Boy Scout in the late 1960s, said in a phone interview with Military.com. "It really means a lot to me that when the family hears that call, they know that the government -- the United States Army, Air Force, Navy, whatever -- is paying the last respects to that veteran for his service."

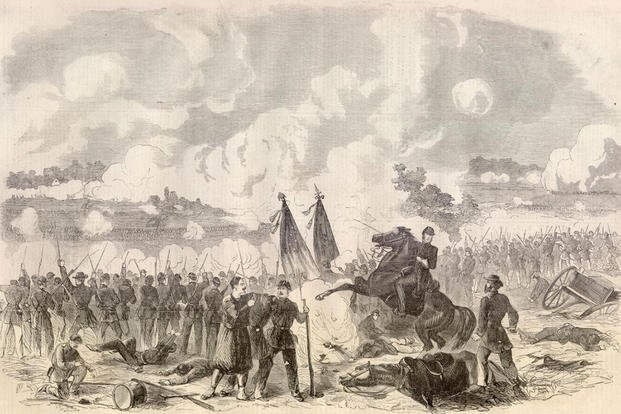

Butterfield was working for a company co-founded by his father -- a little enterprise called American Express -- when he joined the 12th New York Militia; he was serving as a colonel when the Civil War began. In September 1861, he was promoted to brigadier general, and after his unit was transferred to the Army of the Potomac, Butterfield and his men found themselves at the Battle of Gaines' Mill, Virginia, on June 27, 1862.

Part of the Peninsula Campaign -- the Union's bid to capture the Confederate capital, Richmond -- Butterfield was injured at Gaines’ Mill while commanding the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, V Army Corps. Despite the pain, Butterfield would "[seize] the colors of the [Union Army's] 83d Pennsylvania Volunteers at a critical moment and, under a galling fire of the enemy, [encourage] the depleted ranks to renewed exertion," according to his Medal of Honor citation.

The next month, Butterfield and his men camped near the James River in Virginia. While recuperating from his injuries, Butterfield worked on a solution to his "Extinguish Lights" dilemma.

Butterfield lacked any type of musical background, but he was “a little bit of an aficionado of bugle calls,” according to Villanueva; he also was well-versed in Army procedure, as he wrote a manual, "Camp and Outpost Duty for Infantry: 1862," to chronicle a soldier's daily duties.

Taps was not an original composition but rather something inspired by Butterfield's time in the New York Militia, when he learned about "Tattoo," a bugle call signaling the final roll call of the day, Villanueva said.

Assisted by Norton, Butterfield reworked the last portion of "Tattoo" into taps, according to Villanueva.

"When the soldiers first heard it played, it was a much slower call, and it was like a melancholy type of song to them, a way of putting them to sleep," Villanueva said.

Other Union brigades heard Norton's playing of taps and requested permission to play it; the call also spread across battle lines, with some Confederates using it, too. The Army officially recognized taps in 1874, almost a decade after the Civil War ended, and although Butterfield's revision was first played at a military funeral during the Peninsula Campaign, it did not become mandatory at military services until 1891.

The central role that Butterfield played in taps was largely unknown until the late 19th century, only coming to light after a magazine article in 1898, “The Trumpet in Camp and Battle” by music historian and critic Gustav Kobbe, purposely omitted the bugle call because it was unsure of its origin. That piece prompted Norton to write in and explain how Butterfield’s taps came to be, and the bugler encouraged the publication to contact his former commander.

“The call of taps did not seem to be as smooth, melodious and musical as it should be, and I called in someone who could write music and practiced a change in the call of ‘taps’ until I had it suit my ear, and then, as Norton writes, got it to my taste without being able to write music or knowing the technical name of any note, but, simply by ear, arranged it as Norton describes,” Butterfield replied.

Butterfield, who resigned from the Army with the rank of major general in 1870, was buried at West Point in 1901 at the age of 69 despite never attending the U.S. Military Academy. And yes, taps, which has no official lyrics, was sounded at his funeral. More than a century later, Congress recognized taps as the "National Song of Military Remembrance" through the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act.

"Of all the military bugle calls, there is none that is so easily recognized or more apt to evoke emotion," Villanueva said.

More than 1,000 U.S. military veterans die daily, according to Taps for Veterans. To request a bugler, go to tapsforveterans.org; while the nonprofit does not charge for its services, some buglers may request a fee.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.